By Kathlean Wolf

Wild Warner

It was clear something was seriously wrong with the giant that first sank its roots into the ground sometime in the 1890s. Last year, this oak’s neighbor had fallen to the chain saw after a similar loss of leaves signaled illness and imminent death. Whatever the cause, I knew these oaks must be killed and taken away; too many other oaks of great age live nearby, their lives at stake should the disease spread.

I asked to be there when city foresters came to cut the oak down. When I arrived to watch the tree’s removal, the huge oak was already on the ground. The city foresters agreed to donate a few pieces of large limbs for placement at the edge of Warner Pond to serve as climbing spots for children, viewing perches for birders and habitat creation for the park. They also gave me a cross section of trunk for display inside the Warner Park Community Recreation Center.

The year I was born, the oak was a tall, stately youth of about 80 years, scarcely out of oak-adolescence. At 3 years of age, I’d be able to encircle the foot-wide tree with my little arms. Forty-three years later when it fell, the mighty trunk was 3 feet across and nearly 9 feet around, much too large for me to fully embrace for a farewell hug. Young trees appear to grow quite swiftly and older trees to stay nearly the same through entire decades, but the opposite is true. In my 46-year lifetime, the oak had grown roughly 10 times more massive than in its first 80 years.

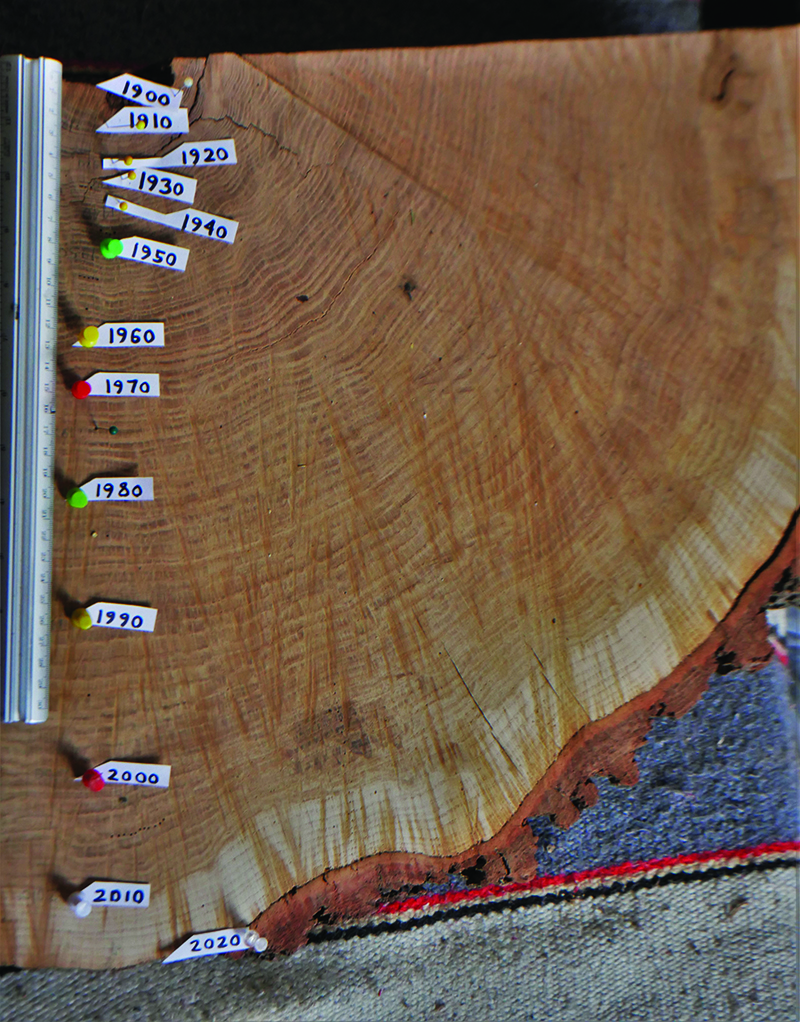

Dendrochronology is the study of tree growth-rings. Scientists have collected “libraries” of tree-rings from all over the world and use them to understand the climate of the past, going back thousands of years. In this age of accelerating climate change, this science can help us understand changing conditions through the study of the rings of our fallen Warner Park trees. I am a novice at it, but I feel compelled to read the story in the rings of our fallen Warner Park trees.

About the same time the recently fallen oak sprouted, the first official measurements of temperature and precipitation began in Milwaukee, where the Great Lakes shipping industry was beginning to take advantage of early storm warnings. A comparison of these weather statistics and tree rings often show a perfect alignment. The dry years of 1920‒1935 yield nearly invisible rings as the oak sapling struggled. The floods of 1993 are marked by thick, dark rings. While tragedy and chaos plagued flooded areas along the Mississippi, the oak soaked up sunshine and great gulps of water to build strong, dense wood. At other times, the story in the rings is a mystery. Cursory searches of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration data and Dane County Lake Level records give no hint of the magical combination of climate conditions that built wide, healthy rings in 1951, 1965 and the first three years of the 1980s.

For humans, the year 2000 was anticlimactic; the various apocalypse predictions didn’t pan out. For the oak, 2000 was the beginning of the end. In the rings we see that something had changed. A radiating streak of yellow running from 2000‒2004 shows the scars of insect damage trapped inside the wood. From 2009 onward, the rings no longer contain the deep brown layer that had gone before, the dense wood that makes an oak so strong.

The stunted growth was invisible to anyone who walked by over the course of the next decade. Two years ago, the first visible sign of trouble appeared: growing from one of the tree’s largest limbs was a large parasitic conk fungus. It could only have invaded a tree already struggling to survive.

Everywhere on earth, tree populations are declining. To keep that sad knowledge at bay, I focus on the trees I know and love. In August and September, I often harvest wild mushrooms from the base of some of these oaks. I consider them friends, much older than I, generous elders who give life to the woods, feeding squirrels and deer with their acorns, feeding soil and protecting small plants and animals with their fallen leaves. Some of these oaks, 300 years old, watched over the councils of the Ho-Chunk before European settlers arrived.

All of Warner Park’s trees are threatened by erratic weather conditions, introduced species and human actions. Heavy vehicles carve deep into wet soil in the springtime, destroying the delicate layer of roots trees use to take up water and minerals. Lawnmowers carelessly chip away basal bark, creating openings for insects to invade, and introducing fungal spores from other areas of the park.

Wild Warner has worked with the Parks Division to reduce mowing beneath some of the oaks, and volunteers have begun spreading native plant seeds in their shade, working to return the soil to good health. Over time, we hope to change park maintenance practices to be more protective of trees young and old. If we are careful with these fellow living beings, those able to withstand the changing climate will continue writing their story in the rings for many decades to come.