By Cora Wiese Moore

Northside News

Growing up near the airport in the Truax neighborhood, Pau Xiong and her family once thought nothing of eating the fish they caught in nearby Starkweather Creek. For years, locals have brought children, dogs and friends to fish and walk alongside the creek. Xiong, a student at East High School, was understandably horrified when she first learned that the creek is contaminated with chemicals commonly known as PFAS, an acronym for per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances. These contaminants have been seeping unchecked from Truax Field into the surrounding ground and surface waters for decades.

PFAS are a group of chemicals used in foaming agents and nonstick coatings that have been linked to a variety of health problems. They are used in firefighting foam for petroleum fires, and for years this foam was allowed to soak into the ground after firefighting drills at Truax Field. Besides reaching the groundwater hundreds of feet below, PFAS were also washed from the ground into the nearby waterways. “Starkweather Creek is not safe,” said Xiong, who works with children at the local East Madison Community Center, located right next to the creek.

The health impacts of PFAS are still being catalogued, even though their toxicity has been quietly recognized for decades, and they have been widely used despite this. They have recently received more public scrutiny, which has kickstarted widespread investigation.

So far, it is clear they have the potential to cause cancer, particularly of the kidney and liver, as well as a multitude of health problems, including reproductive, developmental, and immune disorders. As a bioaccumulating chemical, PFAS is absorbed by your body and then collects over time. Xiong has been working hard to educate fellow students at East High about the health problems caused by PFAS-contaminated water and food. “PFAS can’t be cured. It’s in your body forever,” she said. Xiong is worried about the health of the children she works with at the community center, as well as the people she sees fishing along the creek.

National media coverage and local citizen advocacy have shone a spotlight on the long-standing PFAS plume caused by the use of firefighting foams at Truax Field. In the spring of 2018, members of the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization (MEJO) began advocating for PFAS testing of Starkweather Creek, which flows around the airport. They soon began lobbying for testing of city wells, since PFAS can move quickly through the groundwater. Thanks to their efforts, City Well 15 was closed earlier this year due to the discovery of PFAS levels in the water.

The Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has not yet established a contaminant level for PFAS, but it currently recommends that consumption be limited to 70 parts per trillion (ppt) in drinking water. This is based on the combined presence of PFOA and PFOS, just two of the thousands of toxic PFAS chemicals. Following the example of experts who question the EPA’s recommendation, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services has set a more conservative PFOA-PFOS level of 20 ppt and took action to divert the water of City Well 15 when it tested at 12 ppt earlier this year.

Recommended levels for surface waters like rivers and lakes are different than drinking water standards. Test results from Starkweather Creek, only recently shared with the public, show levels as high as 360 ppt at one creek location. This is 30 times higher than Michigan’s PFOS surface water standard, which is concerning because of PFOS’s particular tendency to build up in fish that might later be eaten by anglers and their families. The bioaccumulation of all the different PFAS chemicals is still being studied.

Maria Powell, director of the Midwest Environmental Justice Organization (MEJO), is also concerned about the foam that gathers at the top of the water. Testing in a river below the Peshtigo Dam in northern Wisconsin showed that PFAS levels in foam can be hundreds or even thousands of times higher than levels in the water itself.

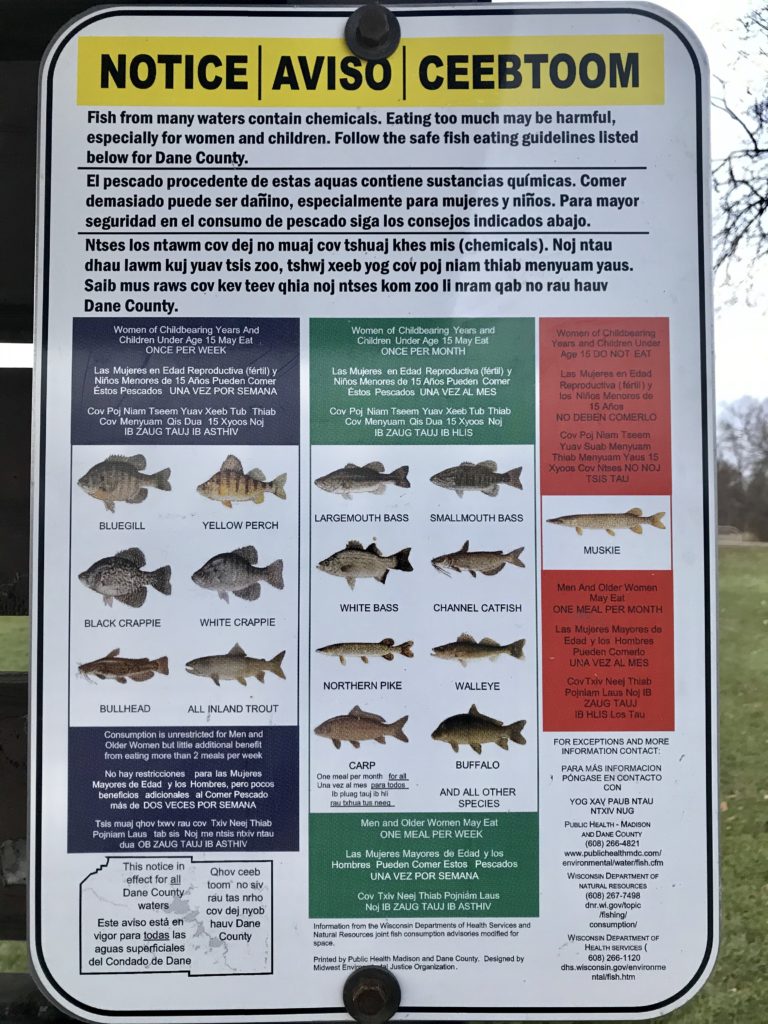

Powell is also concerned about the anglers who fish along the creek. While the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) has said current heavy metal and PCB advisories for fish consumption will be sufficient to protect anglers from consuming too much PFAS, they are not scheduled to make their fish testing results public until sometime in mid-2020. MEJO is currently raising funds to test PFAS levels in the water, sediments and fish independently so this information can be made available to the public as soon as possible.

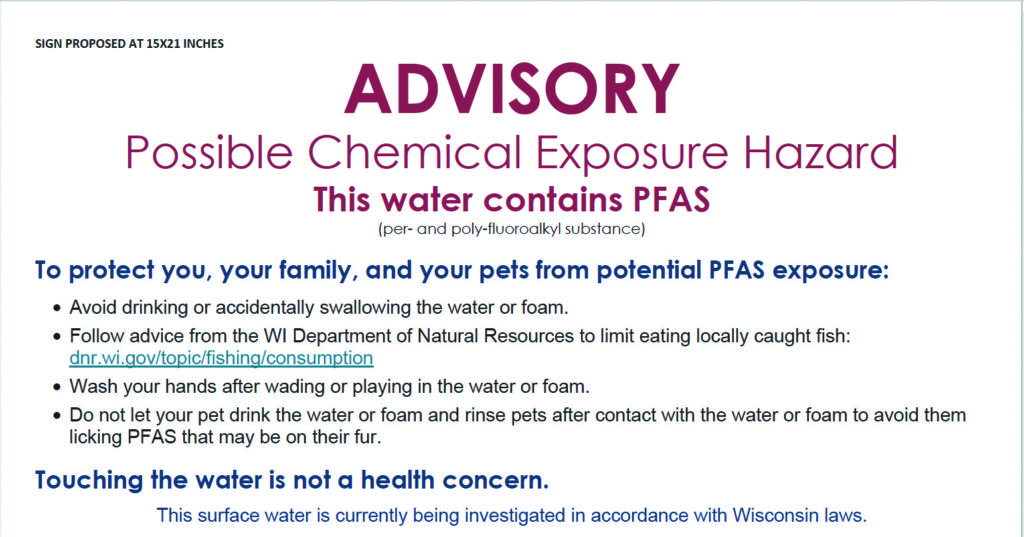

Michigan’s Department of Health and Human Services (MIDHHS) has set a national example in regards to PFAS safety. According to MIDHHS, for children “a health risk could exist from repeated, prolonged whole-body contact with foam containing high amounts of PFAS.” It recommends that nobody, regardless of age, come in contact with the foam. This extends to dogs as well. In contrast, the Wisconsin Department of Health Services has proposed signage for Starkweather Creek with contrary advice that does not acknowledge the potential impacts of PFAS. The proposed signs state,

“Touching the water or foam is not a health

concern,” and “Wash your hands after wading or playing in the water or foam.”

The DNR has been in communication with the Air National Guard, the City of Madison and the Dane County Airport about their responsibilities regarding PFAS clean up at Truax Field for over a year. However, delays and extensions have made even the first steps in this process seem as though they have stagnated. Recent attention regarding the airfield has centered mostly on the proposed F-35 fighter jets, though construction related to this project will also produce a wash of PFAS runoff if the soil contamination at the site is not addressed.

“The Air Force knows they’ve done this,” said Xiong. “They haven’t taken any action, and I don’t think they even will.” Her anger is echoed by other Madison residents who have been paying attention to the PFAS contamination at the airport over the past year. Xiong said her neighbors are becoming more and more worried, but it is hard to engage people from other communities who aren’t directly impacted. “And of course,” she said, “in a low-income neighborhood, no one else would care about this ongoing issue.”

Xiong also said that soon it might not matter. The PFAS plume could already be reaching other city wells and other waterways. “I’m scared for my family, my community, my high school and my future.”

If you want to help, Xiong asks that people research the issue and take it more seriously, even if they don’t live near the airport. More information about the contamination at Truax Field can be found on MEJO’s website (mejo.us/?s=pfas). By keeping up with the issue and speaking up for the communities most impacted by the contamination, Xiong hopes we can keep our neighborhoods safe and healthy.

MEJO’s People’s PFAS Action Team, funded by the Center for Health, Environment & Justice, is looking for residents to join their efforts to hold polluters and government accountable for PFAS pollution in the Starkweather Creek watershed. Please email Maria Powell at mariapowell@mejo.us if you would like to get involved. If you would like to donate to MEJO’s Starkweather Creek water, sediment, and fish testing project, visit mejo.us/testing.